It has now been one whole year since this pandemic started and we got thrown into a quasi-permanent lockdown. Normally, I’d say ‘happy’ anniversary and crack a few jokes to start this up—but it’s best if I abstain myself from doing so.

My deepest condolences to everyone who has lost friends and family to this virus, this is something that should have never been.

A year ago we were told that we only needed fourteen days to flatten the curve, now that we’ve gone a full year of quarantines, lockdowns, masks, social distancing, sanitizing gels mixed with water, and everything else the Venezuelan regime doesn’t even mention the word ‘curve,’ and the nation is as collapsed as ever.

The first days were reminiscent of the worst days of shortages that occurred here during the past decade, with everyone panicking and scrambling to get everything they could possibly afford, that of course, was an occurrence that pretty much replicated all across the globe, we just happened to have experience at it.

The fear and terror felt during the first weeks of quarantine are but a distant memory now, replaced by a new reality that goes hand in hand with our continued entropic and stagnant collapse.

In our double-edged capacity to adapt to adversity, we got over it, and now things have returned to a normalcy with regards to supplies—the problem now is that while there’s plenty of toilet paper, flour, rice, and whatnot, not everyone gets to afford it these days. The memories of teenagers and adults offering masks for sale in exchange for food is not something you’ll ever forget, the hunger that the impoverished majority here feels does not pause because of stay at home or social distancing mandates.

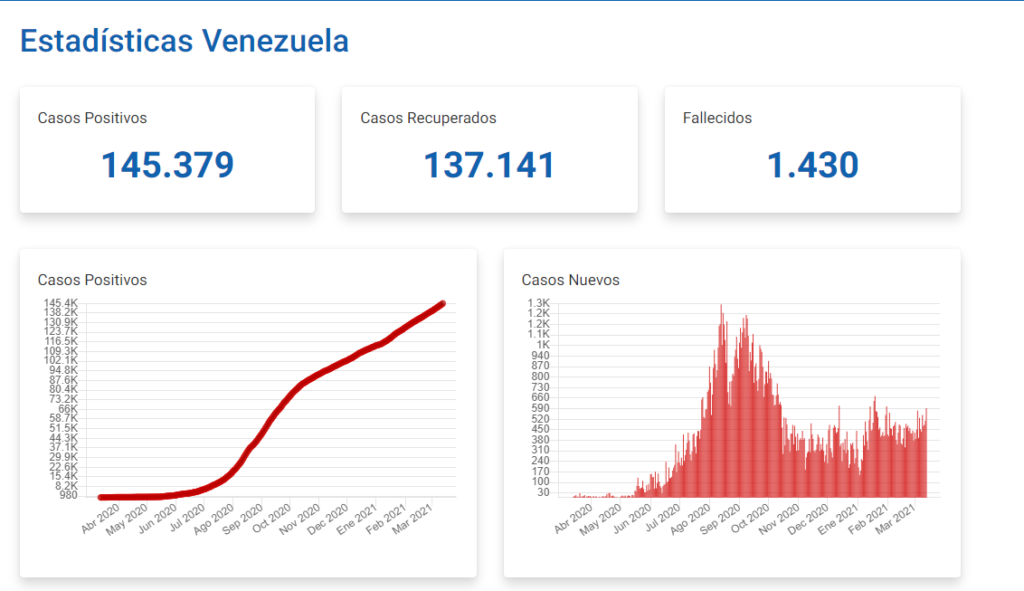

As I’ve been saying for the past year, there’s a glaring discrepancy between the regime’s official tally of COVID-19 cases in Venezuela and what you see and hear from people, as well as the collapsed and over capacity state of certain hospitals.

The official numbers, a year later, are much, much lower than our neighboring countries—not even a tenth of Colombia’s 2.2 million cases reported. Contesting or going against the official numbers can get you in trouble here, so it’s up to you to interpret the incongruences as you see fit.

Two elderly people on the building I live in died to it, and at least five people in my family got it, they all thankfully recovered from it. Things are more rougher in other states, and I’ve had reports from my father that a few doctors he used to know were taken by the virus.

It’s not a matter of living in a constant state of fear of the virus, it’s just that you have to be more careful down here. Public health care here is completely trashed and on its last legs, private clinics are limping as well, and they’ve become far too expensive these days.

We’re entering the first year of lockdown with a ‘Sanitary Fence’ in the city of Caracas and the States of Vargas, Miranda, and Bolivar following an upsurge in cases and the ‘arrival’ of the Brazlian variant of the virus that coincides with a worsening diesel shortage that may or may have nothing to do with it, take that as you will.

One could make the case that the lockdowns have a palliative facet to our ongoing gasoline shortages, lessening their impact.

While the world moves towards vaccination, we’re still way far from that, a privilege mostly reserved for the Socialist Party, military, governors, mayors, and other members of the state—and maybe healthline workers and police officers if there’s some left by then.

The country, a year later

Even without the pandemic being factored it, this was one of the most stagnant years in Venezuela with regards to our humanitarian crisis. Everything that has been occurring continued to occur, multiplied in intensity by the pandemic and all that it has incurred. The flow of migrants out of the country was severely reduced, not because things have improved, but because borders and air traffic have been severely restricted for an entire year, which has not stopped people from fleeing through ‘illegal’ roads that are often dangerous.

That being said, it doesn’t mean that the country was not without its incidents.

From the departure of DirecTV Venezuela and other companies to the worst ongoing gasoline shortages ever, another sham legislative elections, the continued irrelevance of Juan Guaido and the opposition, and tacit confirmations that there is no end in sight to this socialist calamity—the only solution for many is the same one that has always been: flee from here and start a new life, making sure that this disaster never repeats again.

So many stores and businesses have been forced to permanently shut their doors down, others pivoted into ‘essential’ services to remain afloat, for example, clothing stores that now sell food instead.

The dynamics of our economy have always been in constant motion, shifting and twisting to adapt and (d)evolve with the obstacles and shortcomings that arose with each new state of our tragedy—this pandemic being no exception to the rule, but rather, another example of how things move around here, you adapt or you fall behind.

Delivery services are by far the biggest economic boom in times of collapse and pandemic, and they saw a meteoric upsurge in Venezuela ever since the pandemic began. Many inside this country are able to survive thanks to external help (myself included), and that’s a demographic these ‘Grubhub inspired’ delivery services have captured very well.

I particularly have only used them twice to get fast food during one afternoon in December and during my birthday back in January. My budget doesn’t allow for such things and I prefer to cook my own meals anyways.

Their swift success has drawn the attention of the regime, who has already let loose the first signs of their desire to regulate such activities, always masked with good intentions and ‘for the good of the workers.’

Some will tell you that things are better because you can find imported goods and snacks from the US, and because delivery services make good money—but if you look deep down past the Bodegon facade, then you will find the true face of our reality, one still ripe with hunger, hopelessness, and despair.

The grim and depressive mood, another symptom of our demise as a nation, is as vivid as ever. Recently I went to a bakery that’s very well known around this area. Back when I was a child it used to be a very livid place, well stocked, and colorful in its own way. Today, it’s but a pale shard of what it used to be, and everyone in it felt exhausted and defeated. I did my fair share of bread lines there in the past, and yet, people’s spirits weren’t that bad during those turbulent times.

The bread I got was spot on, but the barely stocked shelves, the tense mood, and the sense of despair is but a reflection of the country as a whole.

In the end, people down here are rightfully more afraid of hunger than they are of the virus.

Another death of the Bolivar

The biggest casualty of this year of lockdowns was the Sovereign Bolivar, the third iteration of the country’s currency in times of Revolution. This currency was doomed from the start, showing signs of its impending demise when it barely was a year old, ill-fated to have the same demise as its predecessor.

After one year of lockdowns we found ourselves once again paying millions for everything, despite this new iteration of the Bolivar being a currency with 5 fewer zeroes off its scale than the previous one (which in turn had 3 fewer zeroes).

I haven’t used a Bolivar banknote in more than a year, and the ones that I still have from before the pandemic were already worthless. I make all of my payments using my debit card, as I don’t have access to cash US Dollar notes.

Three new banknotes will start circulation soon, worth 200,000, 500,000, and 1,000,000, with the latter of these only being worth about $0.25 from the get go.

You can make the case that these were bought into existence not as proper legal tender, but to give people exchange, as paying with foreign currencies and getting change back is one hell of a convoluted mess here.

The price of driving

Driving around the streets of Venezuela is no longer a leisure. For starters, you gotta micromanage your gasoline given that it’s no longer virtually free—it’s dramatically more expensive ($1.89 per gallon of non-subsidized fuel if my math serves me right). Subsidized gasoline is hard to come by, and if you do find some then you’ll be wasting hours/days in line for a monthly ration that’s distributed by the regime’s Fatherland system.

That all makes you think twice about giving someone a ride, right?

Furthermore, you have to deal with the constant extortion from corrupt police and national guard checkpoints that seem to multiply with each passing day. Officers can and will stop your vehicle on a whim to ‘inspect’ it, requesting documents or even access to your phone ‘to see if you’re not promoting or spreading hateful material.’

The only way to make it out unscathed is to pay their toll, which of course, has to be in foreign currency, none of that worthless Bolivar.

Such is life down here these days. I’ve been slowly trying to get my mom’s car repaired, but as you can see, I’m in no hurry. That car has given me so many headaches over the past years, if anything, I’ll get it back in operating conditions just in time to sell it towards our escape funds.

Quarantined education

Education remains a complete uphill battle. Children aren’t getting proper education these days, not with classrooms still closed down, a problem that’s not limited to this country for sure, but here, access to e-learning is as tricky as it gets.

If the constant blackouts that plague the country, which are far more intense outside of Caracas doesn’t get them, then the lack of access to constant internet and adequate hardware will.

Our internet sucks, plain and simple, most have to rely on the socialist regime’s ISP and their ancient ADSL technology, made worse by the precarious state of their networking and phone lines. Sure, there are now private ISPs that have amazing 1st-world esque internet speeds in certain cities, but what good is it when they have constant power blackouts, it’s like a monkey paw wish—besides, not everyone gets to afford them.

One of my younger cousins has to come to my house during the weekdays to use my internet connection for her classes because of petty family dramas pertaining who and gets to use internet (which believe me, I want no part of), and even through I’ve had to make constant repairs to my ADSL line, it’s not without problems.

Over the past year I’ve had several problems with the internet in this area, and I suspect it’s all because of the aging phone and ADSL cabling, which makes it very prone to failing during the afternoons. Caracas’ private ISPs just aren’t worth it, in my opinion. Some are very hit or miss with the quality of their service despite their offerings supposedly being ‘faster and better’ than the regime’s own ISP, and other are just plainly ripping people off—I sure as hell don’t have the money nor will ever pay a $750 setup fee and $100 per month for a 10mb line.

And yet, even with my bad internet connection there she is, using a 12 year old hand-me-down

Netbook that has seen better days, giving it her all so that she can complete her high school studies. The only thing I can do is to help her as much as possible so that she continues pursuing her education—and find ways for my brother to resume his studies as well.

Even if schools were to properly reopen tomorrow, children will have to deal with a ruined infrastructure, lack of water, and many other problems. Teachers earn an absurdly low wage here that they might as well not even return, although some will continue to impart education in their classrooms once they’re able to, because that’s what they signed up for in life, for which they have my utmost respect.

A lost year

Let’s face it, we pretty much lost an entire year of our lives to lockdowns. Many lost jobs, opportunities, projects, plans, dreams—and most importantly, friends and loved ones. If it’s any consolation, we’re still here, hopefully in one piece despite everything.

What really gets me bummed down and depressed about this lost year is that the lockdowns left me stranded, losing precious time on my passport’s first extension, and setting me back on my ongoing goal of starting a new life outside of Venezuela with my brother. Over the past three years I’ve fought against every new obstacle in my quest to get my brother out of here (it’s a legal conundrum), but this pandemic was the one thing that there was nothing I could possibly do to solve.

Had none of this occurred then I would’ve been closer to freedom, if not long gone from here already. Nonetheless, this year was all not wasted for me.

I’ve been slowly getting back on track with my plans, and with limited air traffic and a 2-year extension on my passport, the time has come to finish this fight towards a new life away from this country.

Sword’s draft is done, its editing is something I’ll start getting sorted out once my escape plans begin to take more tangible form. I will begin work on Sins soon, and there’s some interesting and unique things coming soon—which I still am not in the liberty to speak about, but for sure I’ll be able to soon, some of which are very closely related to my inexorable escape from this country, that much I can say.

My personal health well, I’ll take the L, I completely failed to improve it during this past year, that’s on me. But I did try my best to make the most out of this stranded year by learning new things and helping others to the best of my ability—but it’s way past due time for me to start getting healthier, I can’t keep going like this or I’ll crumble before I get my visa stamped.

The dread of isolation

The thought of spending time at home away from everyone and everything was something that at first I shrugged off with ease, I mean, after all, I am a social outcast, a loner that has always been at the fringes, or an ‘abnormal’ as people within my mother’s side of my family often catalogue me.

I even shared my personal thoughts about this forced lockdown isolation back when it all started, and all of it still remains true. And for the most part, things didn’t change much for me in that regard—but man, it really started to hit me hard recently, I am only human after all. I do have a lot of mental baggage that I’ve been carrying for the past years, and this lonely isolation has started to leave its mark on it.

Things will get better, I’m sure.

On the 'new normal'

This whole thing has been tough for everyone, and it’s been one hell of a marathon here, because Venezuelans have had zero chance of respite over the past years with all that’s happened, happening and will continue to happen here.

I want to live a normal life one day, that’s what I want to build for my brother and for myself once we’re outta here. I don’t aspire to much beyond that, and to be able to find the means and resources to help others as a force of good, even in this, new, restricted, and complicated reality that we all face.

Venezuela will continue to remain as it is, with no solution to our political, societal, and economical crisis wrought upon by the socialist party and its regime, facing a pandemic with whatever means we have, and struggling with our day to day shortcomings, blackouts, water rations, hyperinflation, and everything else.

There’s not much I can do, I will continue to pray and hope that every single one of you remain safe and sound, and that things improve in all regards soon, so that one day sooner than later, we get to meet under the same skies, my frens.

I do have one piece of advice, whatever your stance is with regards to the use of masks, if you’re pro or against their use is irrelevant to me, just please don’t wear them like this:

Take it easy, stay safe, and God bless you all.

Until the next one

-Kal