Allow me to go back to Monday, the 22th of July. It started as your regular run of the mill Monday; nothing extraordinary despite having a rather exhausting morning and sparse raining. I walked around trying to find a working ATM in this area, I withdrew the max allowed amount per day: Bs. 3,000 ($0.26 at the time), and I carried out with my things.

I lucked out on my way home and walked past a bakery that was about to put out their afternoon’s limited production of bread, I got some of that hot and delicious stuff and continued my journey back home.

At last, I arrived home at around 04:00 p.m., got a much needed glass of water and started cooking a simple meal for my brother and myself before I further went down the list of things planned for the afternoon before our daily 30 minutes ration of water kicked in.

Just like every other Monday for me, right? Nope. A few minutes before I finished cooking and that’s when it happened: Venezuela was struck by yet another nation-wide blackout.

If you live in any other place of Venezuela besides Caracas then you probably weren’t even surprised by it, after all, daily blackouts are part of the new Venezuelan normal—it’s been like this in some places for years now. You know the state of our power grid is bad when Caracas (a city that’s being held in a somewhat functional state at the expense of the rest of the country) was hit by it as well.

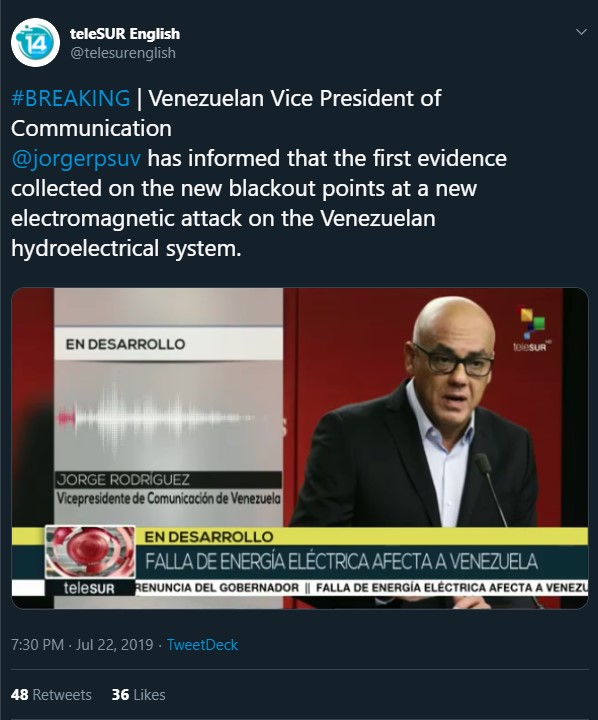

Once again, the regime was swift in placing the blame on America for this new blackout, so swift that they didn’t even bothered to concoct a new excuse or even present evidence. The “Electromagnetic attack™” narrative was repeated once more.

The truth, the unspoken one, the one that the regime will never admit, is that this, along with every previous major blackout and the dire state of our power grid, is all on them.

This ongoing collapse is the end result of years of mismanagement, embezzling, and lack of investment ever since the regime nationalized the service in the name of their Socialism of the XXI Century.

And now we’re paying the price of their incompetence.

As I mentioned above, blackouts aren’t something new in most regions of Venezuela, they’ve had to suffer blackouts that can last days even—my beloved Zulia is one of the most affected, to the point that its a borderline inhumane situation now.

In the case of those living in Caracas, it gave us a slapping reminder of the grim reality of the rest of the country beyond this city’s limits, where daily blackouts are the norm. We just happen to live in the seat of power of the regime—and for Maduro’s regime, the seat of power must be kept functional no matter the cost, even if it means sacrificing the rest of the country.

With my plans ruined, no way to do something remotely productive, and no way to even communicate with anyone, I did what we’ve been doing on every blackout: Lock everything up and just lay in the bed. The refrigerator was not to be opened unless it was absolutely necessary.

Once again, a sort of mass solitary confinement is how I’d describe that afternoon and evening. The chirping sound of insects was all the white noise you could hear. No children playing in nearby buildings, no cars, no stray dogs or cats (come think of it, I hear them less these days); not even the sound of the rather noisy neighbors upstairs.

The sound of gunshots in the distance, which after two decades of living in this city are no longer cause of alarm or amazement, you just don’t get near a window and that’s all.

Given the absurd disparity between the cost of candles and the actual cost of power bills in this country, not everyone can afford them or are willing to freely spend that much on them (a large candle costs more than what I’ve paid in power bills this year). With this fact stemmed from the brilliant management of our socialist regime in one hand and with the fact that necessity is the mother of all inventions in the other, a relative imparted me the knowledge required to craft my own oil candle.

An empty glass jar, cooking oil, water, and leftover cotton from my mother’s medical supplies. These callbacks to ancient times have become rather common in Venezuela.

Once night fell there wasn’t much to do but to lay on bed, stare at the ceiling, and think until I drifted into sleep. The pitch black and an idle mind makes up for some deep interpersonal thoughts, regrets start hitting you, and existential dread ensues.

My brother gets rather uneasy during blackouts; even if he doesn’t outright say it his body language says it all, it took some time for him to ease up and try to get some rest. I had no idea how long the blackout would last (since one of the previous ones lasted about 36 hours). Power did came back to this area at around 1 a.m., by then my sleeping schedule was rather messed up.

By the time I manage to sleep again another blackout hit us; power returned at around 1 p.m. on Tuesday; I only managed to sleep two hours or so until that Tuesday evening, as if I wasn’t behind enough on things I’m now also severely behind on sleeping hours as well.

All schools and work activities were suspended on Tuesday the 23th, and the 24th was a National Holiday (Simon Bolivar’s birthday). This delays my personal (and escape) plans once more, as I can’t proceed with the next phase until I obtain one more document (in another town), which I’m in the process of obtaining.

The rest of the tale following the return of electricity is one that I’m beyond tired of: unstable ADSL internet connection, poor cellphone reception, and the most annoying one: a delay in the return of running water to this area; this is the third week in a row where we’ve had water distribution issues. It’s been years since the regime implemented a water rationing schedule that they don’t even respect anymore.

All in all and after all is said and done, this was yet another demonstration of the utter collapse of our country, a reminder of the despair that has become normal beyond Caracas, and a reminder that no short term solution can be seen on the horizon, given the utter stagnation of the political crisis while everything continues to crumble and fall apart.

As if we hadn’t enough to deal with, everyone has been living in constant fear of a blackout that will ruin your day, can’t even try to stock much food or you may risk loosing it should you have to go for days without power.

Another thing I would like to remind everyone of is that every time there’s a power outage in a region or a nation-wide blackout, the Bolivar is effectively dead as a currency. Paper cash is worthless and its not really viable to purchase anything meaningful; without power you can’t use your debit cards or do wire transfers. When that happens only foreign currencies are what you can use to pay for stuff here—thus, the highly desired cash US Dollar becomes the de facto driving force of the economy even if the large majority does not have access to it.

As of the time of writing this, we’re at five days since we last had running water. I will now wrap this up a few minutes since we have another 30 minute ration of water to do dishes, shower, and refill bottles and buckets—my brother and I have this quasi-choreography for this routine.

Until the next blackout.

-Kal